Spotify Internship Report

From June to September 2019, I took a break from my ongoing PhD and worked as a Research Intern at Spotify in London. I was under the supervision of Simon Durand and Tristan Jehan as part of the music intelligence (MIQ) team. Their work is also similar to my PhD, focused on applying machine learning to music signals in an effort to make computers able to understand musical properties, such as classifying whether a music piece has singing voice in it or not, so this was a good match for me to get to know how it’s like to work in industry in my field.

Jam night at Spotify New York

Jam night at Spotify New York

Overall impressions

Overall my experience was very good. Spotify has lots of energetic, ambitious people that are happy to help out and collaborate with you (on that note, many thanks to Simon, Tristan, Sebastian, Rachel, Andreas, Till, Aparna, and probably more that I forgot!)

Compared to my usual PhD work, this made me especially productive - I worked a lot during these months, but enjoyed it at the same time. Add to that many (mostly optional) meetings such as “Research weekly”, talks from invited researchers, and so on, as well as a great IT infrastructure that puts powerful compute at your fingertips and increases your work efficiency, and you have a very engaging atmosphere that extracts the most out of everyone’s potential.

I also had great freedom in terms of selecting the topic I wanted to research. This is not a given at all considering interns are often bound to one particular task during their stay.

Unfortunately, Spotify had their London offices restructured at the time, so I worked in a temporary office building that was a bit bland in design compared to the nicely designed and decorated main offices. However they were still very high-quality and a big step up from some of the buildings at my university!

Since much of the MIQ team works in the New York offices, I was also able to visit them for a week, with all expenses sponsored! It was great to meet all those people in real life that I only saw in video-conferences until then. Offices there are quite big, and even offer daily catering and in-house music events such as a jam night.

During my stay, I investigated methods for

- separating singing voice from accompaniment

- detecting what is being sung in a music piece (lyrics transcription)

- and when it is being sung if the lyrics text is already given along with the music piece (lyrics alignment).

Better objectives for singing voice separation

For separation, people often use very simple loss functions (e.g. an L2 norm between the predicted output and the real one) to measure the error, which they then minimise to train the system [1], [2]. The problem is that those do not necessarily align with how a human listening to, let’s say, a separated vocal track, would rate the output quality. In other words, the simple loss function can be low, while output quality is rated as bad, and vice versa. This means we are not optimising our systems to maximise the actual listening quality! Evaluation metrics such as SDR [3] or PEASS [4] share similar issues, and are also more complicated to compute or possibly unstable to use for training.

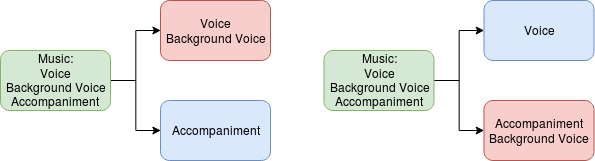

The above losses and metrics also assume that for every music input, there exists exactly one true source output as solution for the separation task (uni-modal). But that might not be the case - if music has background vocals for example, there are two solutions for singing voice separation that both make sense: one that puts the background vocals into the accompaniment track, and one that puts them into the vocal track along with the main vocals:

These monotonic objectives would take whatever option happens to be in the training dataset, and reward the separator more the closer it gets to that solution. This means the other option is punished severely, and the separator might, instead of representing both, be encouraged to predict an average of the two solutions, which however can be a bad output in itself.

We investigated GAN-based training as a potential solution, and also performed perceptual listening experiments (with great help of Aparna!) in an effort to develop a better objective function that more closely resembles how humans would rate the output quality of such systems.

Combining singing voice separation and lyrics transcription

Another idea explored in my internship is concerned with the interactions between tasks: Maybe we can separate voice better if we know what is being sung. And similarly, if we know the isolated voice track, detecting what is being sung should be much easier!

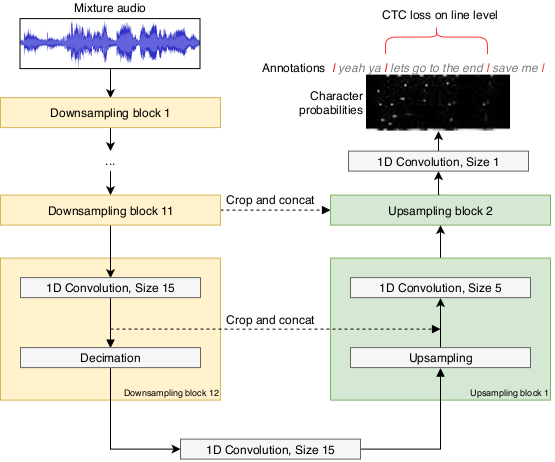

Therefore we looked at multi-task learning to build models that perform separation and lyrics transcription at the same time. We chose the Wave-U-Net [2] model since it already performs separation, and since we hypothesised that its generic architecture allows capturing many time-varying features on different time-scales, including those useful for transcription. We simply take the output of one of the upsampling blocks whose features have an appropriate time resolution (23 feature vectors per second in our case) to directly predict the lyrics characters over time (at most 23 characters per second). To learn from the start and end times for each lyrical line given in our dataset, we apply the CTC loss in these time intervals (see our publication on lyrics transcription and alignment for details).

Branching off a Wave-U-Net upsampling block to predict lyrics characters (source) . The later upsampling blocks for separation are not depicted here

Branching off a Wave-U-Net upsampling block to predict lyrics characters (source) . The later upsampling blocks for separation are not depicted here

Although we hoped to improve performance this way and tried out many different multi-tasking strategies, the multi-task models were only very slightly better, if at all, than their single-task counterparts. We don’t know exactly why, since there are many factors that can influence the results: Possibly the datasets were so big that the single-task models already underfit, so extra information from other task was not beneficial, or the tasks do not overlap so much after all, or we used the wrong multi-tasking strategy, etc. So we did not investigate further.

Also, we found that lyrics transcription is very, very hard! This might not be very surprising, since it could be seen as speech recognition, which is already hard, but with a lot of additional noise (from the accompaniment), slurred pronounciation and other unusual effects due to singing differing from speech.

Lyrics alignment

Since very good lyrics transcription seemed still out of reach, I also tried to use the transcription models for aligning already given lyrics across time according to when they are sung in the music piece. This turned out to be much more successful, and much better than state of the art models participating in the MIREX lyrics alignment challenge 2017 [5].

In conclusion, we find that you can train a lyrics transcription system from only line-level aligned lyrics annotations to predict characters directly from raw audio, and get excellent alignment accuracy even with mediocre transcription performance - see our ICASSP publication (preprint available here)!

Lyrics transcription however, can still be considered unsolved for now, and this exciting problem will hopefully attract lots of research in the future.

References

- Singing-Voice Separation from Monaural Recordings Using Deep Recurrent Neural Networks. ()Details

Proc. of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR)

Huang, Po-Sen and Kim, Minje and Hasegawa-Johnson, Mark and Smaragdis, Paris - Wave-U-Net: A Multi-Scale Neural Network for End-to-End Source Separation ()Details

Proc. of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR)

Stoller, Daniel and Ewert, Sebastian and Dixon, Simon - Performance Measurement in Blind Audio Source Separation ()Details

Vincent, E. and Gribonval, R. and Fevotte, C. - Improved Perceptual Metrics for the Evaluation of Audio Source Separation ()Details

Latent Variable Analysis and Signal Separation

Vincent, Emmanuel - Details