Bounded output regression with neural networks

Say we have a neural network (or some other model trainable with gradient descent) that performs supervised regression: For an input $x$, it outputs one or more real values $y$ as prediction, and tries to get as close to a given target value $\hat{y}$ as possible. We also know that the targets $\hat{y}$ always lie in a certain interval $[a,b]$.

This sounds like a very standard setting that should not pose any problems. But as we will see, it is not so obvious how to ensure the output of the network is always in the given interval, and that training based on stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is possible without issues.

Application: Directly output audio waveforms

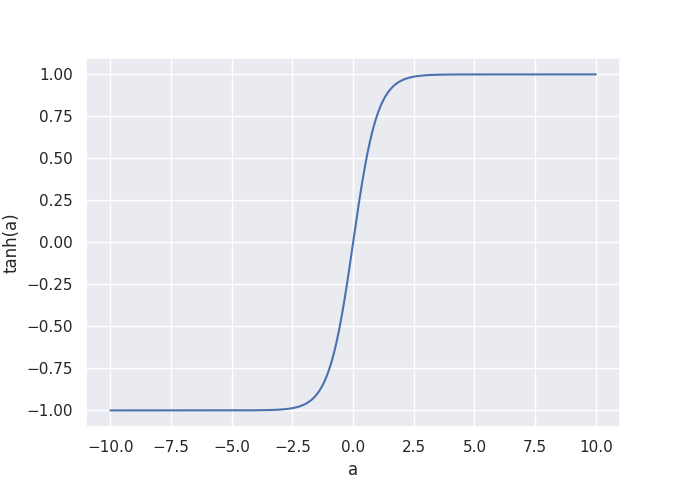

This supervised regression occurs in many situations, such predicting a depth map from an image, or audio style transfer. We will take a look at the Wave-U-Net model that takes a music waveform as input $x$, and predicts the individual instrument tracks directly as raw audio. Since audio amplitudes are usually represented as values in the $[-1,1]$ range, I decided to use $\tanh(a)$ as the final activation function with $a \in \mathbb{R}$ as the last layer’s output at a given time-step. As a result, all outputs are now between -1 and 1:

As loss function for the regression, I simply use the mean squared error (MSE, $(y - \hat{y})^2$) between the prediction $y$ and the target $\hat{y}$.

Squashing the output with $\tanh$: Issues

This looks like a good solution at first glance, since the network always produces valid outputs, so the output does not need to be post-processed. But there are two potential problems:

-

The true audio amplitudes $\hat{y}$ are in the range $[-1,1]$, but $\tanh(a) \in (-1, 1)$ and so never reaches -1 and 1 exactly. If our targets $\hat{y}$ in the training data actually contain these values, the network is forced to output extremely large/small $a$ so that $\tanh(a)$ gets as close to -1 or 1 as possible. I tested this with the Wave-U-Net in an extreme scenario, where all target amplitudes $\hat{y}$ are 1 for all inputs $x$. After just a few training steps, activations in the layers began to explode to increase $a$, which confirms that this can actually become a problem (although my training data is a bit unrealistic). And generally, the network has to drive up activations $a$ (and thus weights) to produce predictions with very high or low amplitudes, potentially making training more unstable.

-

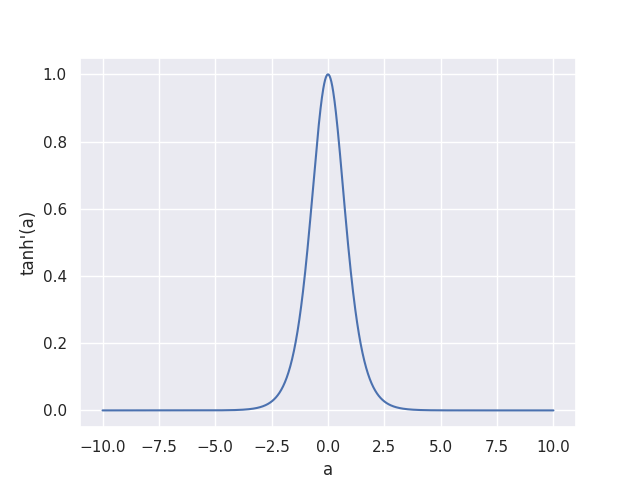

At very small or large $x$ values, the gradient of $\tanh(a)$ with respect to a, $\tanh’(a)$, vanishes towards zero, as you can see in the plot below.

At any point during training, a large weight update that makes all model outputs $y$ almost $-1$ or $1$ would thus make the gradient of the loss with respect to the weights vanish towards zero, since it contains $\tanh’(a)$ as one factor.

This can actually happen in practice - some people reported to me that for their dataset, the Wave-U-Net suddenly diverged in this fashion after training stably for a long time, and then couldn’t recover.

At any point during training, a large weight update that makes all model outputs $y$ almost $-1$ or $1$ would thus make the gradient of the loss with respect to the weights vanish towards zero, since it contains $\tanh’(a)$ as one factor.

This can actually happen in practice - some people reported to me that for their dataset, the Wave-U-Net suddenly diverged in this fashion after training stably for a long time, and then couldn’t recover.

Possible solutions

So what other options are there? One option is to simply use a linear output, but clipped to the $[-1,1]$ range: $y := \min(\max(a, -1), 1)$. This solves problem number 1, since $-1$ and $1$ can be output directly. However, problem number 2 still remains, and is maybe even more pronounced now: Clipping all output values outside $[-1,1]$ means the gradient for these outputs is exactly zero, not just arbitrarily close to it like with $\tanh$, so the network might still diverge and never recover.

Finally, I want to propose a third option: A linear output that is unbounded during training ($y := a$), but at test time, the output is clipped to $[-1,1]$. Compared to always clipping, there is now a significant, non-zero gradient for the network to learn from during training at all times: If the network predicts for example $1.4$ as amplitude where the target is $1$, the MSE loss will result in the output being properly corrected towards $1$.

I trained a Wave-U-Net variant for singing voice separation that uses this linear output with test-time clipping for each source independently. Apart from that, all settings are equal to the M5-HighSR model, which uses the $\tanh$ function to predict the accompaniment, and outputs the difference between the input music and the predicted accompaniment signal as voice signal.

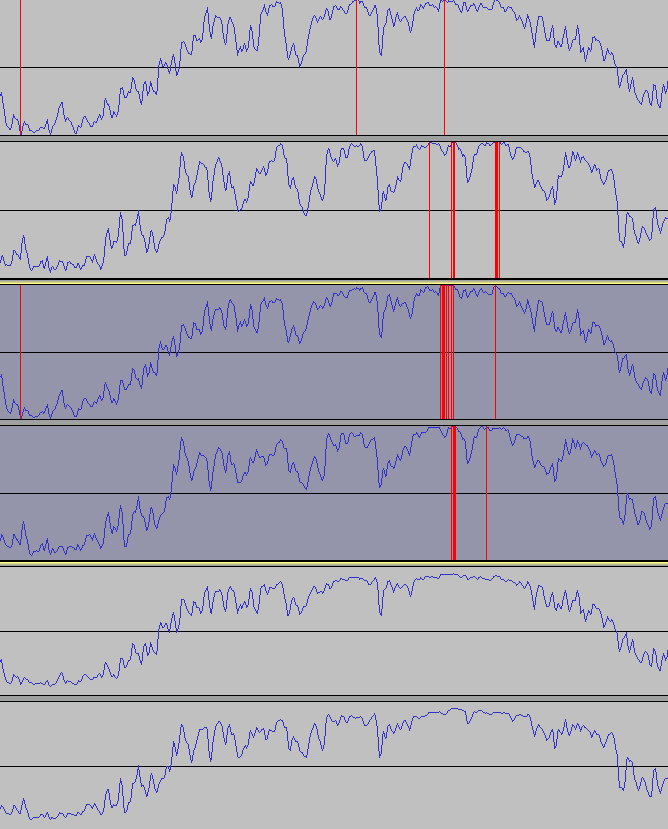

Below you can see the waveforms of an instrumental section of a Nightwish song (top), the accompaniment prediction from our new model variant (middle), and from the $\tanh$ model (bottom). Red parts indicate amplitude clipping.

We can see the accompaniment from the $\tanh$ model is attenuated, since it cannot reach values close to $-1$ and $1$ easily. In contrast, our model can output the input music almost 1:1, which is here since there are no vocals to subtract. The clipping occurs where the original input also has it, so this can be considered a feature, not a bug.

We can see the accompaniment from the $\tanh$ model is attenuated, since it cannot reach values close to $-1$ and $1$ easily. In contrast, our model can output the input music almost 1:1, which is here since there are no vocals to subtract. The clipping occurs where the original input also has it, so this can be considered a feature, not a bug.

The problem with the accompaniment output also creates more noise in the vocal channel for the $\tanh$ model, since it uses the difference signal as vocal output:

- Original song

- Tanh model vocal prediction

- Linear output model vocal prediction

Outlook

Although we managed to get improvements over $\tanh$ to output values of bounded range with neural networks, this might not be the perfect solution. Output activations such as $\sin$ or $\cos$ could also be considered, since they squash the output to a desired interval while still allowing to output the boundary values, but training might be difficult due to their periodic nature.

Also, different regression loss functions than MSE might be useful, too. If we used cross-entropy as loss function, it should provide a more well-behaved gradient even when using the $\tanh$ activation, so different loss functions can also play a role and should be explored in the future.